Children and young people with leukaemia and lymphoma: big increases to survival rates

We were started in 1960 by a family who had lost their six-year-old daughter to leukaemia, and so funding research into childhood blood cancer has always been a key part of our work.

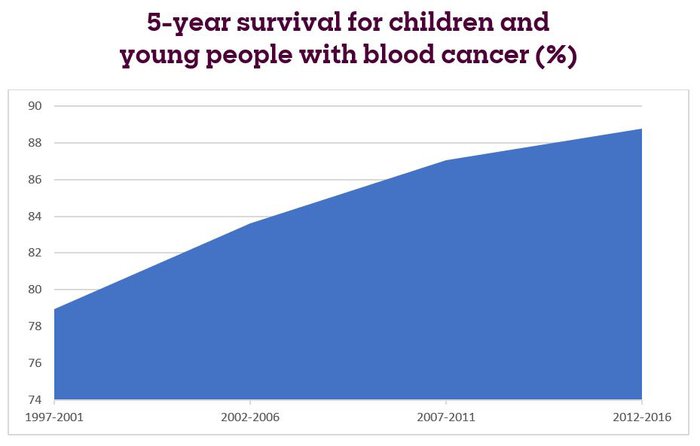

Data from the National Cancer Registration and Analysis Service gives us a good idea of the progress we are making towards beating childhood leukaemia and lymphoma. It shows how the proportion of children and young people surviving leukaemia and lymphoma has changed in the 20 years between 1997 and 2016, splitting the 20 years into five-year periods.

It contains some brilliant news: survival rates increased throughout this period.

Between 1997 and 2001, 79% of children and young people with blood cancer (defined as people aged 0 to 24) survived (as measured by five-year survival). But between 2012 and 2016, that figure had increased to 89%. That is fantastic progress, and it is worth reflecting on what those percentages mean:

- For every 10 children and young people diagnosed in 2012/16, one of them survived who wouldn’t have survived if they had been diagnosed in 1997/2001.

- Between 2012 and 2016, around 700 children and young people with blood cancer in the UK were saved because treatments had improved since the late 1990s.

How leukaemia and lymphoma survival rates have changed

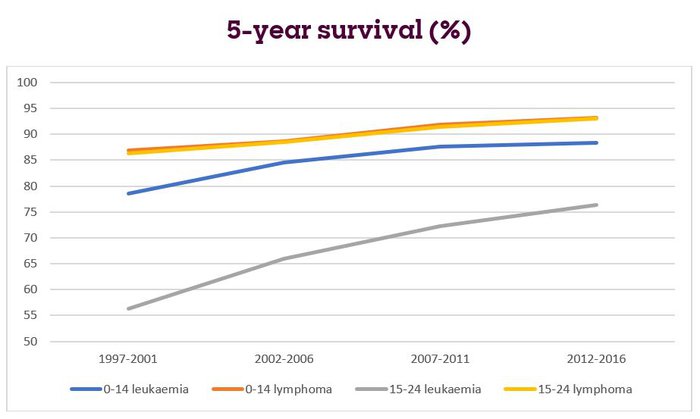

If you look at how survival rates differ between leukaemia and lymphoma, it is a slightly different picture.

For lymphoma, the survival rate for children and young people was quite high even in the late 1990s, and since then we’ve seen small further improvements. In 1997/2001, 87% of children and young people with lymphoma survived, and by 2012/16 this had increased to 93% (and survival for people aged 0 to 14 was about the same as for people aged 15 to 24).

The situation for leukaemia in children and young people was much worse in 1997/2001, when just 79% of 0 to 14-year-olds and 56% of 15 to 24-year-olds survived. But from a much worse starting point, there was lots of improvement over the 20 years and in acute lymphoblastic leukaemia (ALL) we have seen great progress. By 2012/16, leukaemia survival had improved to 88% for 0 to 14-year-olds and to 76% for 15 to 24-year-olds (an increase of over a third).

How survival progress changed since 2000

The improvement in childhood leukaemia survival has been amazing, and we are proud of the role our research has played in helping improve treatments for childhood leukaemia. For example, our research led to the development of the minimal residual disease (MRD) test, a landmark breakthrough that enabled doctors to detect tiny amounts of leukaemia cells and so be better able to make sure each child with leukaemia gets the right strength of treatment for their disease (and helps to predict which children are likely to relapse). Genomic sequencing has also led to children getting better treatment that has improved survival rates.

But as fantastic as this improvement has been, most of the improvement in leukaemia survival for both 0 to 14-year-olds and 15 to 24-year-olds came in the early 2000s, and progress in 2012 to 2016 was slower.

Partly, this is because after the extraordinary progress made in the previous decades, those cases left uncured were the most complex and difficult to find treatments for. It also reflects the fact that for all the progress made, the treatments still used are very toxic and cause a lot of damage to the body (we published a report on this in 2017).

Survival rates for different types of leukaemia and lymphoma

Survival rates vary significantly for different types of blood cancer for 0 to 14-year-olds. There are now some types of blood cancer where over 90% of children and young people survive. In Hodgkin lymphoma, for example, the vast majority of children survive.

But in some types of leukaemia for babies aged under 1, the survival rate is still tragically low, with just 60 surviving. That’s why we’re funding Professor Katrin Ottersbach at the University of Edinburgh to try to find out more about why leukaemia develops in babies, and we’ve also funded the work of Dr Anindita Roy at the University of Oxford. In this age-group, we also need to do much better at improving survival for acute myeloid leukaemia (AML).

It is similar for 15 to 24-year-olds. In some types of blood cancer such as Hodgkin lymphoma, over 95% of young people survive, but for AML the survival rate for 15 to 24-year-olds is just over 60%.

But as low as survival rates for some conditions still is, progress is being made. Every year, more than 100 children and young people in the UK develop AML, and in 1997/01, survival was just 55%. By 2012/16, survival for AML in children and young people had increased to 68%.

Research is key to beating childhood blood cancer

We should celebrate the fact that around 700 more children and young people survived blood cancer between 2012 and 2016 because of improvements in treatments since the late 1990s. Every single one of those lives were saved because scientists had done research. And much of that research was only possible because ordinary people donated the money to pay for it.

But as great as this progress has been, one in 10 children and young people who get leukaemia or lymphoma do not survive. Despite all the progress, in 2012/16 there were still around 800 children whose lives we did not save. And we should also remember that the figures we have used in this piece are just for five-year relative survival and this is not the full picture, as some children will be counted as “surviving” because they live for over five years after being diagnosed but still have their lives cut short.

As a charity, we know far too many parents who are grieving the loss of their child – parents like Miranda Rogers, who lost her son, Ozzie and Elizabeth Anne Holmes, who lost her son, Lee.

But there is real hope for the future, and research is now happening that is helping us better understand why some cases of leukaemia and lymphoma are more difficult to treat or more likely to return. We believe that a world where every child and young person with blood cancer survives is within our reach.

The more research we fund, the sooner we will get there. It’s as simple as that.

So if you, like us, believe that any child dying of blood cancer is one too many, make a donation today.

Fund blood cancer research

The day we beat blood cancer is now in sight, but we need your help to get there.