The story of Dr Jane C Wright, pioneer of blood cancer research

Born in 1919, Dr Wright transformed chemotherapy from an untested, experimental last resort, to a proven, effective blood cancer treatment. Throughout her career Jane overcame prejudice and other barriers to leave a legacy of millions of lives saved.

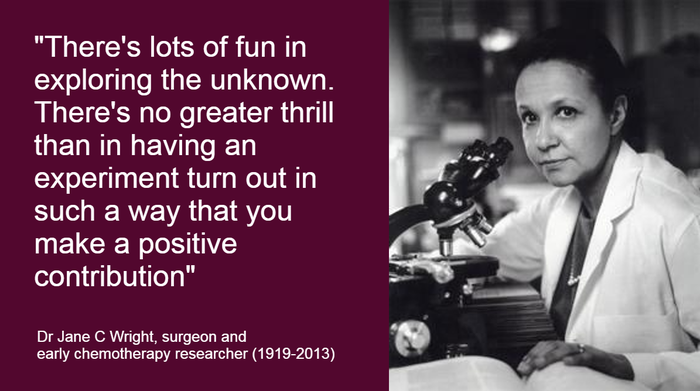

Dr Jane C Wright working in the lab

Defying the odds was in Jane Wright’s blood.

It started with her grandfather, Ceah Wright.

Ceah had been born into slavery. To him, freedom was a distant dream. But the civil war changed that, and when slavery was finally abolished, Ceah defied the odds to earn his medical degree in a country still deeply divided by prejudice.

Ceah died when his son Louis was just three. But Ceah’s determination lived on in Louis.

Louis Wright had to fight harder to prove himself than others did. Despite graduating college with distinction, Harvard Medical School looked at his application with disbelief – they simply couldn’t believe he’d be able pass their entrance exam. But Louis was persuasive, and Harvard would eventually concede that he was a more than capable candidate.

At Harvard Louis was a model student, and he later became the first African American doctor to work at a public hospital in New York City. He spoke out against racial injustice his whole life – he was deeply committed to those who followed him to have the same opportunities that he’d fought to earn.

That indomitable attitude would to spur his daughter on

Louis's daughter, Dr Jane C Wright, was born in Manhattan in 1919, a year before women in America would win the right to vote.

Jane took great inspiration from her father. He believed her talent lay in medicine, but she decided to follow a different path and completed a degree in art in 1942.

The medical profession was almost deprived of one of its leading lights.

But thankfully, just as he’d persuaded Harvard Medical School to accept him 30 years earlier, Dr Louis persuaded his daughter to follow in the family profession.

The art world’s loss was science’s gain

In 1945 Jane graduated from the New York Medical School at the top of her class.

Jane took up her first residencies at a time when there were just a handful of African American doctors. During a time of extreme discrimination, long before the establishment of the civil rights movement, she would blaze a trail for others to follow.

1949 Jane united with her father at Harlem Hospital’s Cancer Research Foundation. Over the next decade they introduced nitrogen mustard agents, similar to the mustard gas compounds used in World War I, to treat leukaemia patients. This research was truly ground-breaking, and Jane would oversee the transformation of chemotherapy from a hypothetical, experimental drug, to an established and effective pillar of cancer medicine.

Jane's research impacted all cancers

Jane’s research had implications much further than blood cancer. She was the first to identify that a drug called methotrexate could be used to treat a range of solid tumours. Methotrexate has since become the backbone of modern chemotherapy, and is still used to this day to treat leukaemia, lymphoma and many other types of cancer.

Jane also championed the development of combination chemotherapy – the use of multiple chemotherapy drugs in varying doses and sequences. This approach was crucial to increasing survival rates for childhood leukaemia treatment, which uses many of the same chemotherapy drugs as it did 60 years ago.

Dr Jane Wright, whose grandfather had been born into slavery, published more than 100 research papers on chemotherapy during her long and distinguished career. And in 1964, she was only woman among the seven doctors to co-found the American Society of Clinical Oncology.

Because research will beat blood cancer

Over 60 years, we've invested more than £500 million in blood cancer research which has led to a long line of breakthroughs that have improved treatments and saved lives.