The Road to Beating AML

In the first instalment of our Road to Beating Blood Cancer series, Professor Brian Huntly talks about the massive changes in research and mindset that have led to today, and what we need to do to get to the point where almost everyone survives.

Professor Brian Huntly

Professor Brian Huntly is the Professor of Leukaemia Stem Cell Biology and Head of the Department of Haematology at the University of Cambridge. Professor Huntly has been working in acute myeloid leukaemia (AML) research for the past 18 years.

Looking back

I’ve been treating patients with AML and studying the disease in the lab for nearly 20 years now, and over that time things have changed massively, particularly in the way we characterise and think about treating the disease.

When I was a junior doctor, we’d diagnose AML by looking at the numbers and visual characteristics of blood and immune cells down a microscope, along with some basic tests that look for signs of the disease. Technology has improved substantially since then, and this has made it much easier to diagnose the disease and understand the changes that drive it.

There have been modest improvements in treatment across this time too. I still remember the improvement we got when we introduced a treatment called ATRA for people with acute promyelocytic leukaemia (APL). When I was a medical student, I was taught that APL was one of the worst possible types of AML, however when we introduced ATRA that was almost completely reversed and APL can now be cured in the vast majority of patients. This has been a great model for other types of AML, as ATRA is a specific therapy and it’s based on the vital principle that if you understand what changes are driving a disease, you can better work out how to treat it.

Improved knowledge has led to modest improvements

And we have improved on this over the last decades. There are many different genetic changes that drive AML, and all these changes give us clues about how the disease will behave. Nowadays, we a know which are the good changes, and which are the bad changes and this information can guide me, as a clinician, on what the most appropriate treatment is for my patients. Today, immediately from the point of diagnosis, we can identify those patients with bad genetic and other changes and ensure that they receive intensive therapy, reducing their chance of relapse. Equally, those AML patients that have some of the good changes can be spared some intensive treatments, such as stem cell transplant. However, the way that we make these decisions isn’t perfect at the moment, but I think that in the next five years or so we’ll know even more about the “type” of disease someone has and how it’s likely to behave, allowing us to tailor their treatment accordingly, which will improve survival.

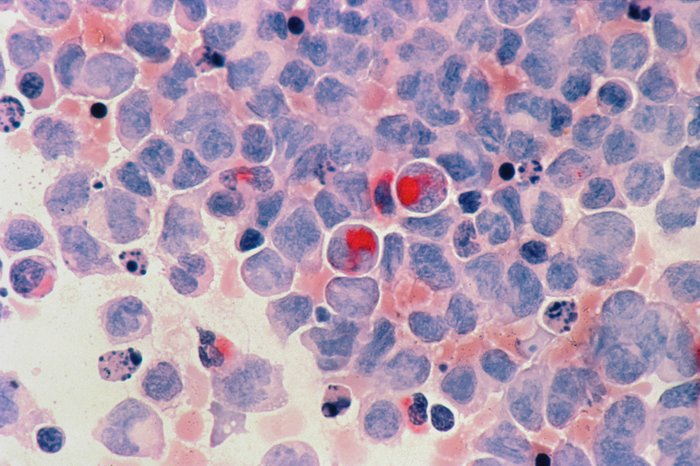

Acute myeloid leukaemia cells under the microscope

We also now have access to tests like the minimal residual disease (MRD) test, that Blood Cancer UK helped to develop, which can identify if there are any leukaemia cells left in the blood following treatment. We used to have to do this by looking at blood cells down the microscope which wasn’t as precise or as successful in telling us who needed what kind of treatment. The MRD test means we can now adapt the treatment we’re giving patients in real time, based on the levels of left-over leukaemia cells in their blood.

We've got a long way to go to improve survival

In terms of treatment for AML, we’ve been less successful. We’re had the same treatment backbone for the last 40 years or so and while we can now identify people who are going to require intensive treatment like a bone marrow transplant, we’ve still got a long way to go to improve treatment for many individual patients. Having said this, we’ve seen new treatments being approved in the last few years and that is really revitalising the field. Many of these treatments target specific changes that are driving the leukaemia and many of them are less toxic than conventional treatment. However, to date, we’ve not seen this translate into improved survival for AML, with older people still only having a 10% chance of surviving for 5 years.

Looking ahead

I think it’s an exciting time and I hope, as we learn more about the disease and which patients need what kind of treatment, we will see things start to improve and we will cure more patients and improve survival for others. This will be easier to do in some patient groups than others. In older people for example, the disease tends to have more complicated genetic changes driving it, and some new treatments or combinations of treatment may prove too toxic. Here I think our focus should be on curing some patients and improving treatment and quality of life for the remainder.

It’s not all about treatment though, as we know that developing AML is a process that can develop over decades before people get any symptoms. There are between three and five “driver” changes that seem to make AML happen and most of these changes occur before people start showing any symptoms. So, I think one of the ways we can think about trying to improve outcomes for people with AML is by either trying to stop it happening or by delaying the process in people who are at high risk. By and large, AML affects older people more, so if we can stall the process, even by 10 years or so, it might be that people die of other things before AML can cause any problems. This is where a lot of our research effort should go into because we all know prevention is better than cure.

There are many different genetic changes that drive AML, and all these changes give us clues about how the disease will behave."

We also need to try to understand how resistance to treatment develops in some people with AML. In general, you have one good chance of trying to control the disease, and that’s when people are first diagnosed. We know that in people whose cancer stops responding to treatment, as soon as chemotherapy is given, changes must happen in the cancer cells that prevent the treatment from destroying them, so if we can work out how this happens, we can think about trying to prevent it. Part of the way we solve this is by developing new treatments and using drugs together in so called “combination therapies”. We think cancer cells have different features and that these features determine how likely they are to respond to treatment. If you can combine treatments and one of these treatments can prevent resistance developing, it increases the chances that the combination will work. This general concept is not unique to blood cancer. All cancers want to do is keep on growing and they’ll adapt to do this however they can.

We have to be driven to make change. I think cancer has taken a bit of a back step over the last few years, compared to the focus on infectious diseases and mental health that have occurred during the pandemic. Something like cancer is a more specific problem, usually to an elderly population, whereas mental health problems can affect literally anyone. I’m concerned that cancer research might slip off the agenda somewhat and that there won’t be enough people to pick up the baton and drive it forward. Having said that, I am incredibly positive to those wanting to come into this field. It’s fascinating, there’s an unmet medical need and there are changes we can make. In addition, helping people is the most gratifying thing you can do. It’s a fantastic career and it’s a job that really makes a different.

We have to be driven to make change."

I think its an exciting time for AML, we have more tools, and our understanding is increasing all the time. We have new drugs, but we still don’t know how best to use them so there’s real opportunity to improve things. If we can achieve these things, in the future, at worse, I think we’ll be able to predict who will get the disease and at best I think we’ll be able to pause its development or perhaps even prevent it. We can only do this through research and by investing in research and researchers. In doing so, I do believe we’ll make great strides for people with AML.