The Road to Beating CML

We've made great strides in CML research thanks to the development of drugs called TKI's. But they don't provide the cure that many people want. In this blog we discuss how we might make this happen within a lifetime.

Professor David Vetrie

Professor David Vetrie is a Professor of Translational Leukaemia Genomics at the University of Glasgow. He is a leading light in the field of CML and contributed to the discovery of three genes that are now known to be vital for CML stem cell function.

A decade of the same treatment

I’ve worked in chronic myeloid leukaemia research for more than 10 years now and, truthfully, standard treatment for CML in that time hasn’t changed.

Perhaps that’s shocking to read, given that we have identified new ways to target cancer cells, but it’s because when tyrosine kinase inhibitors like imatinib (TKIs) were introduced 20 years ago, they completely transformed CML as a disease. These wonder drugs meant that a disease that was previously fatal was now one that was highly manageable. They set the benchmark so high that it’s been difficult to bring anything into clinic that improves that!

Before we had TKIs, the survival rate for CML was poor and the gold standard of care was a gruelling stem cell transplant, but only a proportion of patients qualified for this.

Back then, only around 20% of patients would survive for 10 years with the disease, now that’s more like 90% and people have a pretty much normal lifespan, which is fantastic.

Treatment works and works well, but it doesn’t give people a cure

But despite TKIs transforming how we treat the disease, they do not cure the disease for the vast majority of patients, and we’ve been working to make sure that one day, it can. The downside of TKIs is that people have to take these drugs every day for the rest of their lives and that in itself comes with implications for both patients and healthcare systems. Patients can experience side effects and for the UK, it’s a strain on the NHS to pay for these drugs.

It’s definitely not ideal, which is why we want to be able cure CML and get people off treatment long-term. Yes, it would be great if in my lifetime we could say 100% of people with CML could just be given TKI’s and would have a normal lifespan, but really we want to go beyond that and get patients off treatment and to stay in remission permanently, so they can live a life without thinking about cancer on a daily basis.

Who will see their cancer return?

At the moment, only around 10% of people with CML are able to come off treatment. These are people who have the best response to TKI treatment and are people we hope stay in remission. Some people do, but for others, unfortunately the disease does return. The million-dollar question is: why do some stay in remission and why do some relapse?

And the answer? Well, currently we really don’t know.

But this population of people provide us with a really exciting question to study: what is unique about their disease which means they can come off treatment and stay in long-term remission – compared to those who would see their disease return if they came off treatment (which I’ll discuss a bit more later).

So, 10% of people can come off treatment but 90% can't. These 90% of patients can be split broadly into three different groups and for these people there are specific questions we need to address.

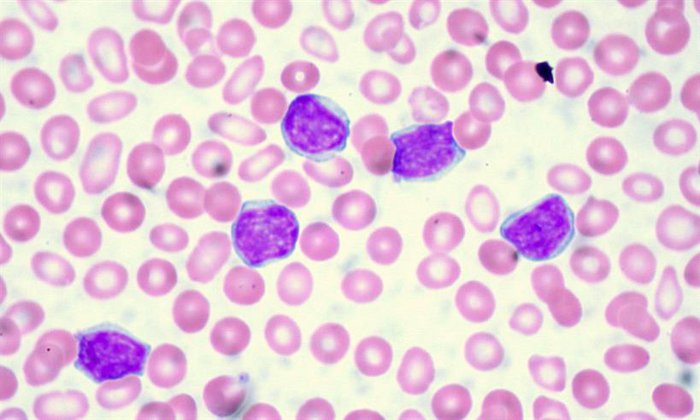

CLL cells viewed under a microscope

Some sneaky cells manage to avoid treatment

The most common type of CML is something we call chronic phase CML. These people respond well to TKIs but aren’t able to come off therapy because they're likely to see their disease return due to lingering cancerous cells that are known as CML stem cells. We’re unsure why a small proportion of people are able to come off treatment, but the majority aren’t, and we think this is because some of these CML stem cells manage to avoid being destroyed by treatment.

In people who come off treatment, there must be something that prevents the leukaemia cells from growing again. If we're able to work this out, then we’d have a strategy to try and get more people off treatment – by developing drugs that imitate the “good” qualities we see in the 10% of people who come off treatment. This is an active area of research for many researchers, myself and my colleagues here in Glasgow included.

We need new drugs for people who don’t respond to standard treatment

The second category is patients who don’t respond very well to TKIs, which is about 25-30% of people with CML. It’s much harder to manage the disease in these people and there’s a risk that their cancer will mutate to a more aggressive form of CML, which is called blast phase CML. Having said that, for this group we're seeing new treatments being developed that could help manage the disease better.

For example, asciminib is a new drug that is also a TKI but works slightly differently from currently used TKIs like imatinib. In clinical trials, it has been successful at managing the disease in this group, which is an exciting breakthrough that we could see in the clinic very soon. Overall, our goal for people who don't respond as well to TKIs is to understand why this is and then find new drugs to treat these people – or work out how we can reverse this process of treatment resistance.

The last category is people with CML in blast crisis. If these people don’t qualify for a stem cell transplant, then their prognosis is poor. While this is a minority of patients, it’s important we find new strategies to treat this type of CML as this will be key to getting to the day when everyone with CML survives.

We have three main questions we want to answer

So, these are the three main research questions we need to answer to take us to a cure:

- How do we come up with treatment strategies which imitate “good” leukaemia stem cells to get more people off treatment?

- How do we overcome resistance to TKI’s?

- How do we develop new treatments for blast phase CML?

If we can do these three things, we can make CML curable in a lifetime and give people a lifespan similar to the rest of the population. Technologies are helping us so much these days that I really do believe this will happen.

For starters, I think we’ll have the answer to the first question about why some people stay in remission off treatment and others don’t in the next five years. Whether we’ll have the treatments we need to imitate this process in others is another question, but I do think we’ll have the answers to start making this happen. My hope is that we'll develop tests that will allow us to identify and predict which patients are likely to stay in long-term remission, if we were to stop TKI treatment. That would be a huge achievement!

A blood cancer researcher uses a pipette to study a sample in the lab

Research holds the key that will unlock these answers

Research is the only way we’ll answer these questions and for that we need one vital thing: funding. Blood Cancer UK acknowledges the importance of all blood cancers but it’s not necessarily the same elsewhere. Some funders think that because CML is in a better position than other types of blood cancers, funding should be prioritised elsewhere, and this could potentially stall progress.

It’s correct that other blood cancers have a poorer prognosis, but we still have questions we need to answer before we can cure CML.

We need to make sure the research community don’t move on to other challenges in the field, and stay in CML research. I'd argue that investing in CML is vital, as it’s a good model for many other types of cancer. It’s one of the simplest forms of cancer and if we can’t cure the simplest forms, what hope do we have of curing the others?

We also need to take into account that because more people are living longer and surviving the disease, the number of people living with CML is increasing year on year. The overall number of patients living with CML over the next 30 years will take it from one of the rarer forms of leukaemia to one of the most common forms. For that reason, I’d argue it’s essential to continue to fund research.

The other barrier is because CML is a rare disease, having access to samples from people with the disease to study in the lab is more difficult and studying real samples is the best way to understand the disease more. We're always grateful to the CML community who provide us with the samples we study in the lab.

Curing CML within a lifetime

But if we overcome these barriers, there is clear progress to be made and I do think we can get there. I can honestly say with my hand on my heart that the CML research population in the UK and internationally are some of the most dedicated people I know and are passionate about eradicating and curing CML. Ultimately, it’s the patients and people who support charities who fund research who inspire us to continue to do the work we do. The money you donate will be put to good use to try and reach a point in time where CML is a disease that is cured for all patients. I’d like to be able to say that we’ve achieved that in my lifetime.