The Road to Beating MDS

Drawing from four decades of experience, Professor Ghulam Mufti explains how things have changed for people with MDS throughout his career, the exciting progress made in genetics, and how we'll go about curing MDS on a global scale.

Professor Ghulam Mufti

Professor Ghulam Mufti has been a blood cancer researcher for over 35 years. Professor Mufti specialised in myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS) and acute myeloid leukaemia (AML) and was awarded an OBE in 2017 for his services to blood cancer medicine and research. He put together the first set of criteria that is able to determine how someone’s MDS is likely to progress that is now used worldwide.

Looking back

I started out my career in MDS in the 1980s when I was a junior doctor at Hammersmith hospital in London. That means I’ve been involved in treating and understanding the disease for almost four decades and there is no doubt, particularly in the last decade, that there have been significant advances in our understanding of why the disease occurs, how it starts, how it develops and which patients are likely to have a better outcome.

Transformational moments

Throughout my career, there have been several moments that have changed the field that stand out to me. The first is when we did the first reduced intensity transplant at King’s College Hospital/King's College London for MDS. This is a stem cell transplant with less intense treatment beforehand, which is important because MDS is more common in older patients who are less able to tolerate more toxic therapies and so we were previously unable to give them stem cell transplants.

I was part of the team that put together this less intense conditioning treatment and trialled it in people with MDS at King's College Hospital. I remember presenting that data at the prestigious conference, American Society of Haematology (ASH), in the USA. I could see and feel the excitement on the faces of the audience who knew that what we had done would help make a significant difference for people with MDS and give more people a chance of cure. That was a truly humbling moment.

The second transformational moment for me was when a drug called lenalidomide came along. For a specific type of MDS, this drug had and continues to have a huge impact. People with a specific type of MDS (called 5q-syndrome) struggle to produce normal red blood cells and previously needed to go to hospital every three – to four weeks for blood transfusions. But lenalidomide promotes the production of red blood cells and is so effective that patients who respond no longer require blood transfusions. This made a big improvement in their survival and their quality of life.

I could see and feel the excitement on the faces of the audience who knew that what we had done would help make a significant difference for people with MDS and give more people a chance of cure."

I also remember treating the first person in the UK with azacitidine, a drug that slows the progression of the disease and extends survival for people with MDS. This felt like a game-changing moment and has made a real difference for many people, but sadly not everyone responds to treatment like this and eventually, patients’ relapse. Combinations of 5-azacitadine with a variety of other drugs are now being successfully trialled globally, with very promising results which I hope will extend survival for people with the disease even further. However, a bone marrow transplant still remains the only curative treatment. Far more allogeneic transplants are being done across the world for MDS, but it’s not an option for all patients and in the majority, our strategy is to control the disease rather than cure it. It is clear there’s still a long way to go for patients with MDS.

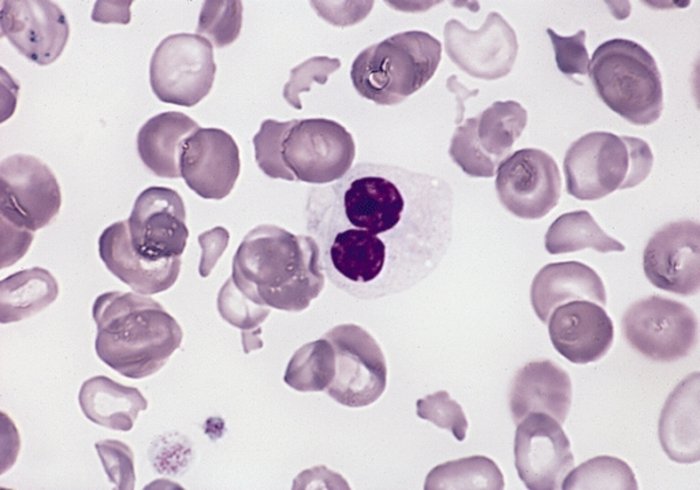

MDS cells viewed under a microscope

Looking forward

In the coming years we’ll learn even more about how we give stem cells transplants safely, which will allow us to give them to even more people. I also hope we’ll learn how to reduce the chance of relapse following a stem cell transplant. For those who are not eligible for a transplant, our increased understanding of the genetic basis of the disease will drive forward the creation of new targeted drugs and immunotherapies that will allow us to treat patients in a much more tailored way, according to their specific subtype.

We already know that there are some genetic changes that make some families more likely to develop the disease. Similarly, we now know far more about the changes in genes that drive the disease. That’s a piece of work I am hugely proud to have been a part of as I think this work will be a footprint for drug discovery that will have a huge positive impact on what is to come.

We have incredible technologies available to us now that will help us understand more about the changes that lead to the disease developing. We’ve got more to understand about how our risk of developing the disease changes as we get older, and more to understand about the role of the “microbiome” (bacteria in our gut). This is a relatively new area of research but the microbiome is thought to play a role in the development of a number of different cancers.

Changing our mindset

Whether we’ll be able to cure everyone is still debatable and there are some fundamental things we need to understand before I’d be confident of this. For example, as we get older, we know that some blood cells start to change. This is called “clonal haematopoiesis of indeterminate potential” (CHIP). Our bodies create new blood cells all the time, but as people age, some of these new blood cells mutate and form clones of themselves that look and act differently to normal blood cells.

This can lead to the development of blood cancer and studies have shown that individuals with CHIP are more likely to suffer from heart disease, stroke and diabetes. We also need to identify individuals where this process is happening and monitor them to see if the process turns into blood cancer. If we can do this, then we might be able to learn how to prevent the transformation of CHIP to MDS. I think changing into a mindset of prevention is important and think this should be a key area of future studies.

Blood cancer researchers in the laboratory

We can't leave people behind

As long as there is funding to do the research, I am confident we’ll continue to make progress and deliver new treatments in countries like ours, but elsewhere around the world I don’t think it will be the same. We’ve seen what’s happened over the last few years with the pandemic: countries who can afford to buy vaccines buy them and use them first, leaving developing and poorer countries behind. Sadly, it is the same for cancer treatments. There are still countries that can’t afford drugs like lenalidomide that I’ve described above. Transplants are much less common in developing countries because people can’t afford it, so people are missing out on potentially lifesaving treatments.

It’s something not often talked about, but the disparity between the Western world and developing countries is huge and the repercussions are tragic. A single course of 5-azacitadine costs thousands of dollars. People sell their homes to get extra months of life and when funds have been used up, tragically the treatment stops and with it the life of that individual stops too. The problem is likely to continue as we make more breakthroughs and create exciting, but expensive new treatments and global leadership in this area is lacking. If we can address this, we may have a shot at curing this disease on a global scale.

The disparity between the Western world and developing countries is huge and the repercussions are tragic"

Looking back at 30 years of my involvement with MDS, there is no doubt in my mind that research has saved and will continue to save many lives, and I want to say thank you to everyone who donates and makes this research happen. Even a small contribution makes a huge difference. I could give hundreds of examples in MDS where research has helped us introduce new drugs into clinical practice. With no research, none of these treatments would have been possible. So many lives have been saved. If that isn’t a good enough advert for doing your bit to fund research, I don’t know what is.

Interested in hearing more?

Be the first to hear when we publish the next in the Road to Beating series

We will keep you updated about our work and the ways you can help, including campaigns and events. We promise to respect your privacy and we will never sell or swap your details.