People with blood cancer now account for 1 in 20 new Covid intensive care patients

This has added to our concern that the vaccines aren't working as well for people with blood cancer as they do for other high-risk groups.

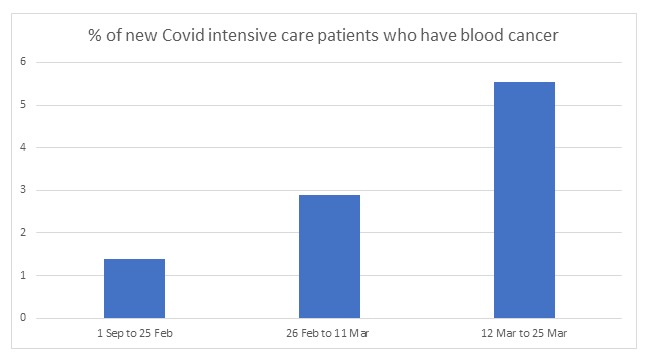

Data shows a sharp rise in the proportion of new admissions with blood cancer

1 in 20 people who are admitted to intensive care with Covid now have blood cancer as an underlying condition, according to our new analysis.

The analysis, based on data from the Intensive Care National Audit & Research Centre (ICNARC), shows a sharp rise in in the proportion of new admissions who have blood cancer.

Between September 2020 and the end of February 2021, one in 68 people admitted to intensive care with Covid had blood cancer. But from March 12 to March 25, this had increased to more than 1 in 20.

Despite this, the risk of people with blood cancer becoming seriously ill with Covid is now much lower than it was two months ago because the lower infection rate means far fewer people are contracting it.

Why has this happened?

We believe that people with blood cancer now accounting for a higher proportion of intensive care admissions could be a sign that the vaccine is not working as well for them as it is for other high-risk groups.

This is something we have been concerned about for some time, as people with blood cancer have weakened immune systems and so vaccines tend to work less well on them.

The new findings also support the findings of research published last month showing that people with blood cancer who had had the first dose of the Pfizer vaccine were much less likely to produce Covid antibodies than people who did not have cancer.

We need to know how effective the vaccines are for people with blood cancer

We have responded to this news by launching a new fundraising appeal to raise money to fund research to find out how well the vaccines work for people with blood cancer.

By analysing blood samples from people who have had the vaccine, we hope to learn whether people with different types of blood cancer or who at different stages of treatment are more or less likely to get protection.

This could mean that people who are most likely to respond well can start returning to normal life, while people who are unlikely to respond can continue to take precautions to avoid the virus.

Gemma Peters, Chief Executive of Blood Cancer UK, said: “For most people who are vulnerable to Covid, getting a vaccine will mean they can start thinking about getting back to normal life. But this new analysis highlights how people with blood cancer may be less protected by the vaccines and so they will be unsure of how careful they still need to be.

“The good news is that the lower infection rate means people with blood cancer are now much less likely to come into contact with Covid than they were a few months ago. But Covid will be with us for the foreseeable future, and so the increase in the proportion of Covid intensive care patients with blood cancer means it’s vital we understand how much protection they are likely to get from the vaccines.

“The Government has not funded this research properly, and so we need to rely on the generosity of the British public to give people with blood cancer the answers they need. The more money we can raise to fund this research, the clearer the answers we will be able to give people with blood cancer about when they are likely to get back to normal.”