The Road to Beating Lymphoma

From the introduction of "remarkable" monoclonal antibody treatments, to modern day CAR-T therapy, Professor Peter Johnson looks at how scientists have successfully targeted lymphoma, and how they'll bring about the day when no one dies of it.

Professor Peter Johnson

Professor Peter Johnson is a Professor of Medical Oncology within Medicine at the University of Southampton. He was Chief Clinician for Cancer Research UK from 2008-2017, Director of the Francis Crick Institute cancer research network 2017-2019 and is currently National Clinical Director for Cancer at NHS England. Peter specialises in the treatment of lymphoma and lymphoma research and was involved in a key clinical trial called REMoDL-B which led to a new way of classifying lymphomas.

Looking back, I've seen treatments transform survival rates

Over the course of my career, we’ve seen a big improvement in survival from non-Hodgkin lymphomas and that’s because of a couple of different things. First, these days we are much better at defining what type of blood cancer someone has. We know we need to treat Burkitt lymphoma in a different way to diffuse large B cell lymphoma (DLBCL) and in a different way to mantle cell lymphoma.

Added to this, 20 years ago we saw the arrival of monoclonal antibody treatments such as rituximab, and these have improved outcomes hugely. If you look at survival graphs for non-Hodgkin lymphoma, there’s a notable improvement at the point where rituximab was introduced which is really striking. Mortality that was previously high suddenly began to fall.

Rituximab was a game-changing drug for people with lymphoma

Everybody who was treating patients when we first got access to rituximab could see what this drug was about to deliver. For those with low grade lymphomas, for years we’d looked after a large number of people who would have some treatment, go into remission for a while, relapse, have some more treatment, and so on until the treatment was no longer effective.

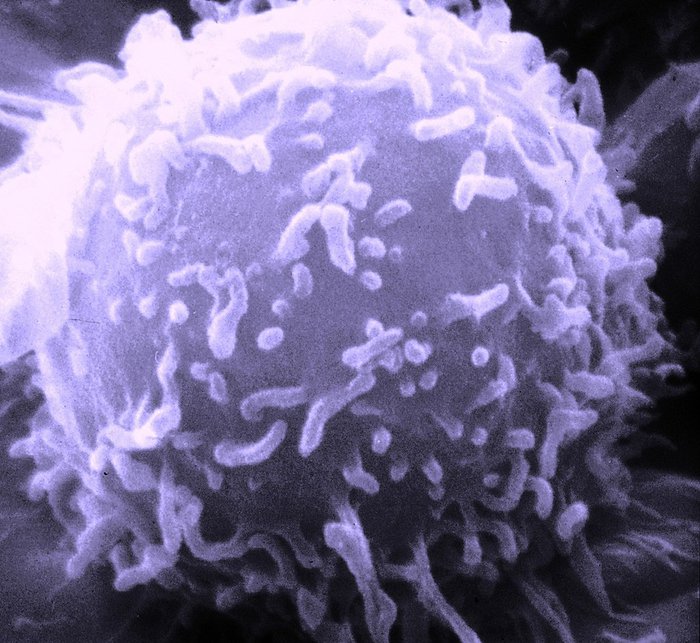

A microscope image of a single human lymphocyte

When we introduced rituximab, we saw people who had lymphoma and were desperately unwell as their illness had stopped responding to chemotherapy suddenly get better, and that was remarkable to see. It’s what gets oncologists out of bed in the morning – thinking that the research we do will make a tangible and visible difference in the clinic.

Progress since then has been mixed

Since then, we’ve been trying to refine our understanding of these diseases even further to improve outcomes. We’ve had mixed results. I think of making progress towards beating lymphoma as being a triangle – there are three points we need to address: understanding the illness; working out how best to test for it; and creating new treatments. We have a much better understanding of the illness and the genetic changes that occur in lymphomas thanks to new technologies, but we’ve not yet been as successful as we would like in translating this knowledge into new treatments for things like aggressive lymphoma. There are some targeted treatments such as lenalidomide and ibrutinib that really help some people with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, but we’re struggling to define precisely who they will help most.

When we introduced rituximab, we saw people who had lymphoma and were desperately unwell as their illness had stopped responding to chemotherapy suddenly get better, and that was remarkable to see."

Looking forward: New therapies and refining current treatments

So while we’ve made progress, there have certainly been bumps in the road. I think in the next few years we’ll start to see further step changes in survival for people with lymphoma. For example, CAR-T cell therapy and bivalent antibodies are newer treatments that both harness T cells to target lymphoma cells. These treatments are already starting to help people with difficult-to-treat disease, such as those who see their disease return or those whose lymphoma stops responding to conventional treatment.

For low grade, slow growing lymphomas, the question is still open as to whether we’ll get genuinely curative treatments or whether we’ll see a continuation of what we have at the moment, which is an extension of the period of expected survival but with the disease still needing treatment from time-to-time. I still hope that even without fully curing the disease, we may get to a stage where someone with lymphoma still has the same life expectancy as someone without it.

An aging population presents new challenges

Hopeful as I am that we’ll continue to see improvements for people with lymphoma, there’s one big thing we need to consider that could make things more difficult. We have a progressively aging population, and the average age at diagnosis is going up, which is presenting us with a whole different set of challenges. We are seeing more and more people in my clinic who are over the age of 80 and have been diagnosed with aggressive lymphomas. If they were 40 or 50, we’d stand a very good chance of curing them, but for someone over the age of 80 who is frail and has other health problems, it’s much more of a challenge. It’s also much harder to get good research evidence in older people because they need such an individualised approach to treatment due to other health problems they might have. That’s some of the most challenging medicine we do now.

A blood cancer researcher at a work station in the lab

One of the ways we can improve this is by using less toxic therapy, and we are getting better at doing this. In low grade lymphoma, we’re increasingly using targeted treatments that are easier for older patients with other health problems to tolerate. There are emerging treatments like bivalent antibodies that we’re just at the beginning of understanding, and they look like the sorts of treatment that we’d be able to give to people who aren’t fit for intensive chemotherapy. So, over the coming decades, I think we’ll get better at treating people with other health problems, and I hope that lymphoma will follow the direction of something like childhood leukaemia, where we see cure rates continue to go up and up.

A bumpy road ahead?

As confident as I am that we will make progress, there are still barriers for clinicians if they want to develop an academic career. The requirements of graduating medics these days are so much bigger than previously, and there seem to be few opportunities for them to learn about active areas of research, making it much more challenging for someone coming out of medical school to know what is happening at the cutting edge of science. The way we train doctors is rigid: We teach them to adhere closely to guidelines and protocols. This comes from a desire to assure the quality of care, but it drives out a lot of creativity, which is essential in research. The pressures on the service in the NHS also that mean clinicians are seeing more and more patients, and this makes it even harder to carve out time out for research. We need to address these things if we want to keep doing effective clinical research.

What’s really clear is that if you want to improve human health, you have to invest in science. That’s the only way we’ll make progress. The answers won’t fall off a tree – they have to be dug up and found out by scientists and by investing in science and our workforce, even if it takes a while to deliver, it puts us in the best position to make advances. We can see that in the last 30 years there has been an increase in survival, some of the improvements have been outstanding and that’s purely down to long term investment in research thanks to organisations like Blood Cancer UK. I’m confident we’ll continue to make progress, and that investing in research is the best way to do this.

Interested in hearing more?

Be the first to hear when we publish the next in the Road to Beating series

We will keep you updated about our work and the ways you can help, including campaigns and events. We promise to respect your privacy and we will never sell or swap your details.